What

to look for in a good Tai Chi teacher

The

Movement is Clear

When exhibiting,

the observer should be able to distinguish each technique that comprises each

movement in the Tai Chi form. The teacher

should be able to break down each movement into a series of steps when

teaching.

As an example,

“Cloud hands” will always have three distinct techniques: 1) Step 2) Shift weight & block 3) Turn waist to deflect

In this example,

the weight shift is crucial because it allows the practitioner to “root” into

the step and put power into the “block”.

However, it is not uncommon to see this movement done with the block before

the weight shift, even by masters.

Unclear movement

derives from lack of ongoing correction for at least the first decade, sloppy

practice, or having learned in a sub-optimal manner by simply following.

Unclear movement

and careless teaching results in greater and greater dilution of the art over

generations. Therefore, the approach to

teaching and practice should be rigorous.

Good

posture

It’s impossible

to over-emphasize the importance of good posture in exercise and martial

art. Good posture means different things

in different arts—grapplers and western boxers stand in distinct ways, often

hunching, because of the body mechanics in those systems.

In Chinese

internal martial art the head and spine must be

straight because all power derives from the “dantien”.

By dantien we mean the waist and, more specifically, the root

of the spine. If the back is not straight, the dantien

cannot act effectively as a fulcrum to utilize leverage and direct internal

power. Constant whole

body connection is required to maintain the continual inertia of tai

chi.

Here we don’t

mean ramrod straight, but rather naturally

straight. [Link:

Harvard Health Publishing, "Proper posture the tai chi way",

2018/3/5] There are of course exceptions to every

rule, but one must learn to do things properly first before learning the

exception cases. This holds true for any field or discipline, physical

or otherwise.

Slouching is

unfortunately so common it has become a trope to satirize the weak tai chi

practitioner in “golden rooster stands on one leg” with a pronounced slouch and

the head jutting forward.

Poor posture

indicates careless instruction or sloppy practice. This often arises via

informal teaching, where it can be reinforced over generations. It can also come from teaching the student to

“empty the chest” before they are able to do so without hunching.

Many masters

become quite old and the body naturally stoops. Some

practitioners have a spinal curvature disorder, such as scoliosis. Nevertheless, if you observe true masters and

good students carefully, you will notice they keep their backs as straight as

possible within those physical limitations.

However, students following elder masters will often copy their stooped

posture, thereby diminishing their own practice and expression of the art.

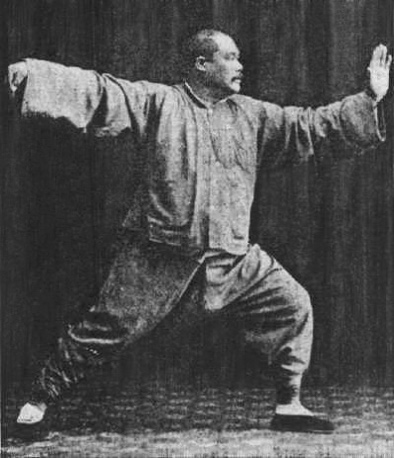

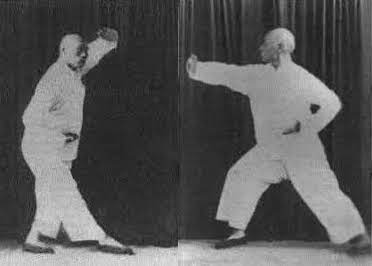

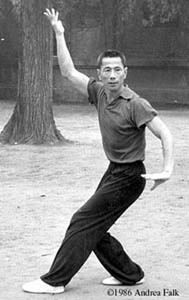

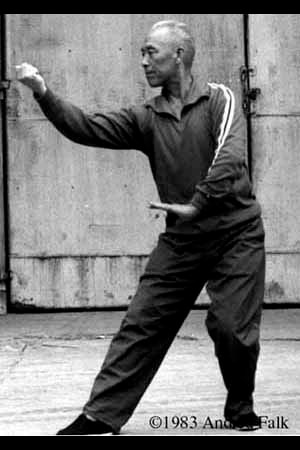

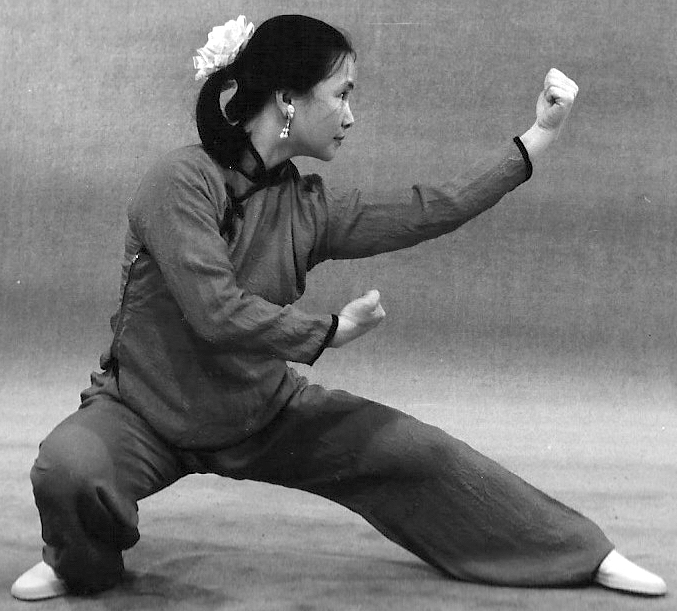

Examples of good posture

in Chinese internal arts

Yang Chengfu

(tai chi)

Fu Zhengsong

(bagua)

Xia Bohua

(bagua)

Xia Bohua

(wudang sword)

Chen Zhenglei

(hsingyi)

Bow Sim Mark (tai chi)

Bow Sim Mark (bagua dragon)

Bow Sim Mark (hsingyi)