This is a matter of some dispute, but suffice it to say if you cock your finger over the guard, thinking the added leverage it confers is worth it, your finger will be cut. If you see a practitioner using that grip, it's an indication of insufficient experience in real Wudang sparring, generally conducted without protective gear.

The general consensus is that:

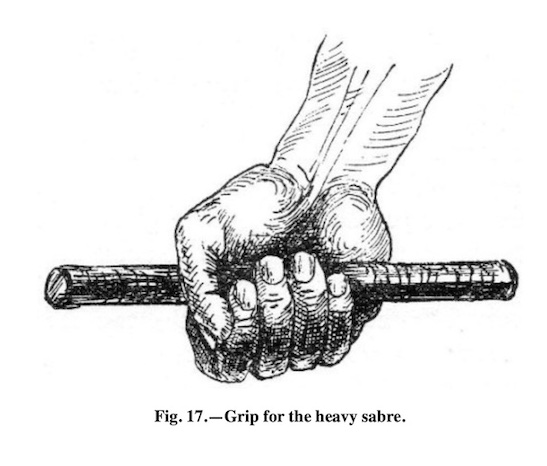

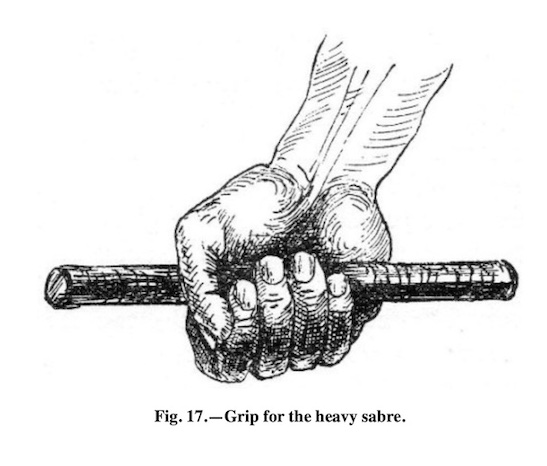

Wudang Mountain might say the pointer finger and thumb. Li Jingling taught indoor students the middle and ring finger. Bow Sim Mark affirmed "Lightly and firmly with two fingers", but wouldn't say which two. "Research," was her answer if pressed. However, this is the jian grip Bow Sim Mark taught:

If there was a gap between the thumb and forefingers, she would disarm you in the blink of an eye.

The above image comes from a European military training manual, Broadsword and Single-Stick (Allanson-Winn, Phillipps-Wolley, 1911).

I use this example instead of a Chinese source to show that real sword art is common across cultures. A tool is a tool and the basic methods of use will be standard. Bow Sim Mark shows this enclosed fist grip in her book Advanced Sword (1980).

Like Phillipps-Wolley and Allanson-Winn, Bo-Sim favored cudgels as the other fundamental weapon.

No nonsense.

劍

Notes: The example shown is for heavier cut-and-thrust broadswords of 2.5lbs and over, with a weaker grip depicted for light cutlass of about 1.5lbs. The thinking is that the quicker, lighter cuts cannot be effected with the heavy grip, but these external stylists are likely using "dead hand" technique suitable for a single-edged hacking weapon. In "dead hand" you grip the handle as tightly as possible because you are charging on horseback, which puts a lot of impact into the weapon on hits, or hacking and pressing with force into an opponent's weapon or armor. In Wudang jian. we can use an active grip in that "Wudang never goes force against force." I put that in quotes, but it's the literal fundamental principle of Wudang fencing. If it goes force against force, it's "Shaolin", which doesn't mean it isn't good or effective. In my experience you need both. This was also my teacher's view. However, Shaolin sword requires significantly greater limb strength and expenditure of energy. To be assured of its efficacy, you need to be strong like Wang Zi-Ping, no excuses.

Wudang internal sword is "softer", requiring greater core strength but less muscle mass because internal art is "all tendon". Wudang fencing is 99% sticky, 99% envelopment, 99% tendon slice, and 100% point. There are no blocks, and only occasional chops, which only require full fist tension for the instant of impact, like hsingyi. For these reasons, the active or "live grip" is viable, especially in Wudang, even on a heavy sword. With sufficient wrist training, all cuts can be made with thumb touching at least the pointer or middle finger, and most without much or any visible modification to the enclosed fist. If you have cheat the grip to get full extension on difficult cuts, you haven't trained your wrist sufficiently. If you do need your thumb to open a little to brace on certain cuts, do it on the handle, not the guard. After spending extended periods training with the weapon, you'll find that much of the control comes just from he tips of the middle and ring finger pressing the handle in opposition to the palm. If fencing with these two fingers, as advised by Li Jinglin, what need to constantly utilize the thumb? Train harder and you'll find it's not necessary. A single exception might be cheating the grip to pose in a cut with extreme twist and wrist flex on a heavier sword, but static positions equal death in real fencing. If fencers can do the advanced techniques on a straightsword of 2lbs and above, which require the "heavy" grip in the picture, how can cheating the grip be justified on less challenging swords under 1lb?

In Chinese straightsword, we generally require our students to learn saber, to get used this strong grip and build wrist strength while developing the tendons for jian. An advantage to a uniform grip such as the active enclosed fist is that, if one gets into trouble and has to block, force-against-force, the grip is secure. Similarly, the wielder is always ready to chop. I can't overstate the significance of this—a modern Wudang fencer can chop straight into your shoulder from a center guard position with no windup or telegraphing using basic hsingyi technique, and then saw forward.

Straightsword is a finesse weapon, but that doesn't mean your grip doesn't have to be secure. What it means is that a stronger and more experienced practitioner can finesse it right out of your hands.

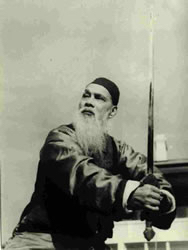

If you are still unpersuaded, or if your instructor is advocating fancy grips, google a photo of Chen Wei-Ming or Wang Zi-Ping, who used sword against guns in the Boxer Rebellion. Here he is at an advanced age showing the internal form of "Incense points to Heaven":

Like all practitioners of real sword art, both show an enclosed fist. When it's for real, you don't mess around.

吳

Transmitted faithfully,

⼥⻨颗

revised 3.23.2023

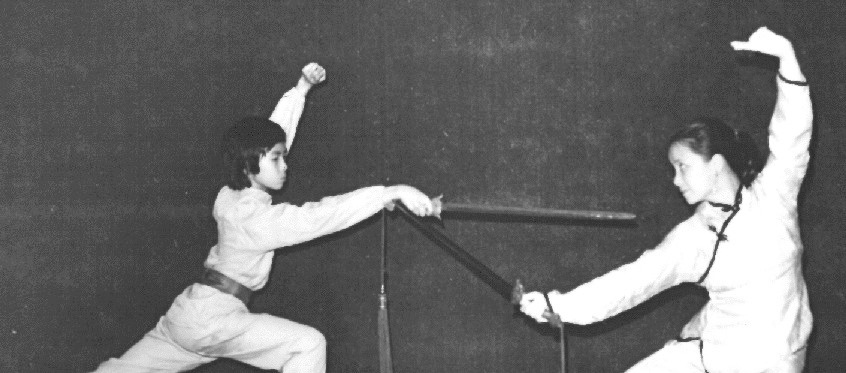

Bow Sim Mark teaching Donnie Yen Eight Section Advanced Sword, which comes from Wang Zi-Ping and other top swords of the first generations of modern Chinese fencing. Although the form can be expressed in the wudang way of Li, for under 30 we teach and practice in the shaolin way of Wang. Certain attacks are best met in this manner, and the shaolin training is critical for thrusting and pointwork in general, too often not emphasized in the wudang practice:

Knight of the Old Republic General Li Jinglin,

gloved and ready to re-establish harmony: