Sword Dance

a

brief survey

"When sorting out

timber for a house, that which is straight, free from knots, and good of

appearance can be used for front pillars. That which has some knots but is

straight and strong can be used for rear pillars. That which is somewhat weak but has no knots

and looks good is variously used for door sills, lintels, doors, and screens."

Likening the Science of

Martial Arts to Carpentry,

The Book of Five Rings [trans. Cleary]

What is Sword

Dance? What constitutes a Sword Dance

done well?

Early

History

We can trace

Chinese Sword Dance back as far as the first Han Dynasty through historical and

pseudo-historical accounts. Although

early histories are not entirely reliable, we have no reason to doubt the

existence of this art form. There are

numerous examples of longswords dating to the periods referenced.

The first Sword

Dancers were soldiers and assassins. A

well-known early account tells of an assassin Xiang Zhuang using a Sword Dance

to try to get close to the emperor Liu Bang. His intent was, of course,

nefarious. Xiang was foiled by the loyal

general Xiang Bo, who joined the performance and matched the would

be assassin’s timing and position to keep him from the emperor. Peter Lorge notes

that Zhuang could not simply push past Bo and still maintain the pretense of

being an innocent performer, and thus the assassination was prevented.[i]

Women in

Martial Arts

Although Sword

Dance may have been largely the domain of male soldiers until later eras,

simply because fewer women participated in war, one of the first named martial

artists in China is General Fu Hou. Her

tomb from the late 12th century BCE was excavated in Anyang in 1976.[ii]

By the Tang

Dynasty, the participation of women in Sword Dance is well documented,[iii]

and this may have contributed to the rise in popularity of nuxia. [iv] These tales of female knights errant in the

Song and later dynasties have become an indispensable fixture of contemporary wuxia,

not least because of Jin Yong’s Lotus[v]

in the contemporary era. It’s hard to

find a high budget sci-fi, fantasy or action series that does not contain a

strong female hero in the mold of Katniss Everdeen. Today the best fencer in US history is Mariel

Zagunis,[vi]

and the “finest living grappler” is Kayla Harrison.[vii] The skills of these women was hard earned,

and their accomplishments great, such that both can be called “peerless”.

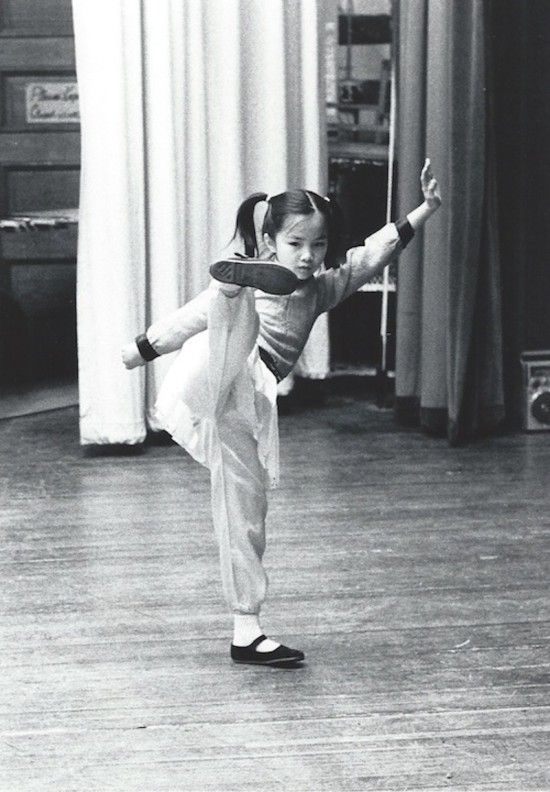

Because so many

women took up martial arts in the modern era, initially predominantly modern

Wushu in China,[viii]

where women have always had a role in warfare for millennia, and in the heroic

literature for centuries, it may be that Sword Dance is now often considered a

primary domain of women. Yu So Chow,[ix]

the daughter of the great teacher Yu Jim Yuen,[x]

was famed for her Sword Dances. She even

made a film called “Black Peony” which title may be a play on the Wudang White

Peony Temple.[xi]

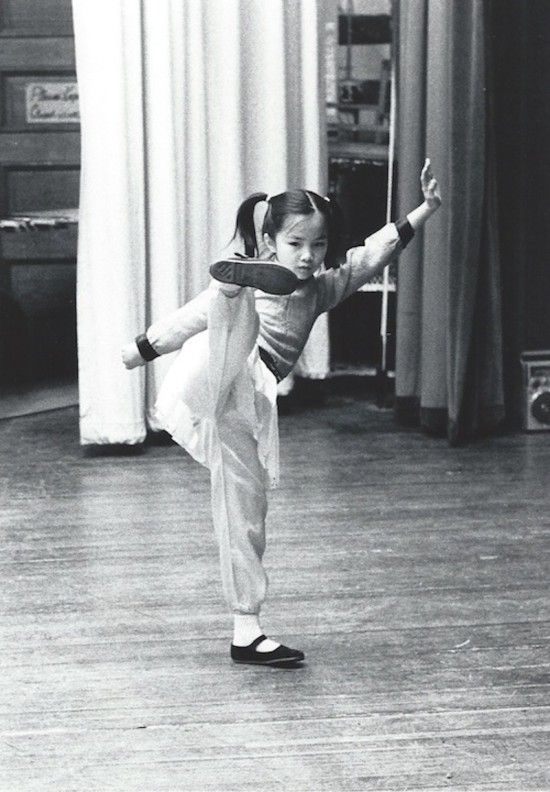

Figure 1

Yu So Chow as "Agile Black Peony"

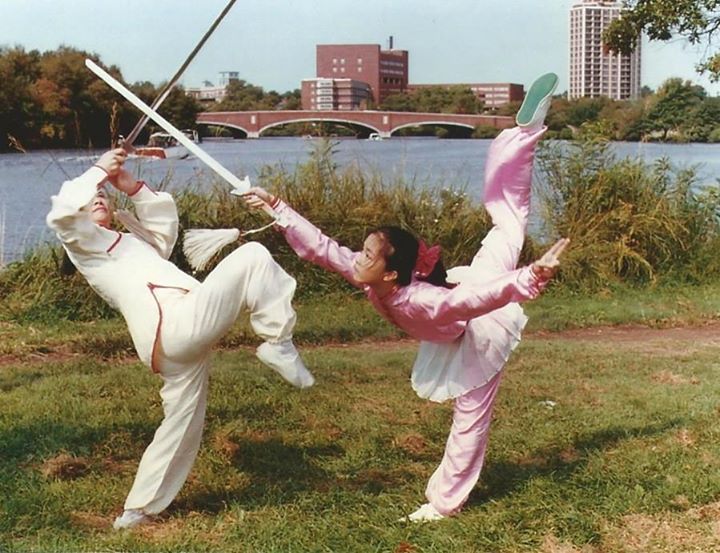

When Bow Sim Mark

completed her decade of wudang training with Fu Wing Fay one of the first jobs

she took was as a Sword Dancer and choreographer at the Miramar Hotel in Hong

Kong. It was a good way to make money,

and scratch her opera itch, while continuing to develop her internal sword

technique.[xii] Unlike teaching, where most of the master’s

time goes into the students, performers get to train all day, every day.

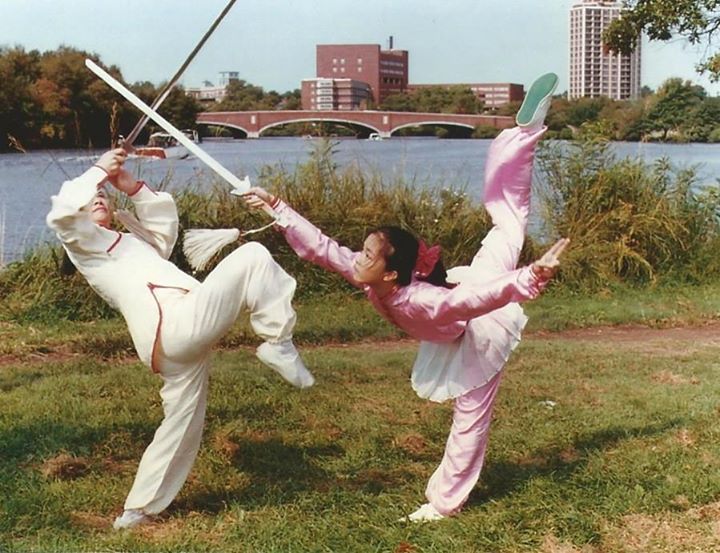

Figure 2 Bow Sim Mark performing Sword Dance at

the Miramar Hotel in Hong Kong

Martial

Arts & Performance Arts

It’s no surprise

then that her daughter was winning medals in international competitions at an

early age, and her son became one of the four Kungfu crossover stars with a

global reputation. Her art intersected

choreography and exhibition in much the same way as Yuen clan[xiii]

and the Lau.[xiv] Bruce Lee also came from an opera family, and

at one time he was the “Cha Cha King” of Hong Kong,

an achievement this great fighter was proud of throughout his life. Is it possible this is a reason he became Ip

Man’s most famous student? The

connection goes even deeper in that many Wing Chun schools now trace their

lineage to the Red Boat Opera Company[xv]—Sammo Hung made a movie about this called Prodigal Son

(1981). So we

can’t say there is no connection between martial arts and dance and

theater. In fact, this connection

stretches back to antiquity, and perhaps beyond.

Martial dance is

part of many traditions including the Māori people, whose warriors

reputation for ferocity may be unmatched.

Capoeira is a martial art routinely practiced to live

music as a form of martial dance, integrating acrobatics, like contemporary

competition wushu. The martial intent

had to be hidden because the art was practiced by oppressed peoples. War dances are a staple of many traditional cultures

from Ukraine to the Zulu, the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt, Scotland

and the Philippines.[xvi] Aspects of dance appear in prizefighting, and

we’ve seen a few Capoeira techniques showing up in mixed martial arts matches

in recent years. The most famous example of dance in combat may be the “Ali

shuffle”.[xvii] Even Bruce Lee adopted this technique to

demoralize opponents with his blindingly fast footwork. Ali himself called his own footwork a

dance. Watching his skip steps in the

ring, it’s hard to disagree. So it’s no wonder Muhammad Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard are

considered the two greatest boxers of all time—their footwork and balance was

next-level; significantly better than everyone else.[xviii]

Fencing, like

boxing, is a rhythm sport.[xix] It all comes down to timing and

distance.

Figure 3 Bow Sim Mark fencing with her daughter

Chris Yen

Modern

Sword Dance

With modern Sword

Dance, at one end of the spectrum you see dancing with a sword in hand. The dancers are typically classically

trained, and in many cases very good.

They may even execute sword techniques better than most martial artists,

because straightsword is a finesse weapon, requiring grace and precision and

excellent posture. In my experience,

professional dancers tend to train harder than most martial artists, but it’s

still not martial art.

At the other end

of the spectrum you have martial artists who play

music while exhibiting routines. This

became popular in recent decades, promoted by famous practitioners like Bow Sim

Mark and others for martial forms beyond straightsword, and today you see it

across styles. But most martial artists

are merely using the music as a backdrop, and not matching the form to the

music in the manner of choreography.

Therefore, it is not true martial dance.

Sword Dance at a

high level requires matching the movement to the music—to the timing, the tempo

changes, and the feeling of the song. It

requires control and adjustment of distance because performances take place in

a bounded space. Most importantly, every

movement and each technique in the set of techniques that comprise a movement

must have martial application.[xx]

I’ll say it

again because it’s so important:

“Every movement in a true Sword Dance must have martial application”,

otherwise you “break the art.”

Ideally, one

should be able to apply those techniques.

For this reason, true Sword Dance is one of the most difficult art forms

to do well. It has the same rigorous requirements as other fine arts, but a

broader scope. There are simply more

dimensions.

Is it good for

anything other than performance?

Arguably, it is. Floyd Mayweather

is considered the greatest technical boxer of all time, and when you look at

his victories, it becomes immediately apparent that his ability to “mess with

his opponents’ timing” is a key to his success.

He’s simply a better “dancer” like Ali and the Sugar Rays—all of these boxers have greater control of timing and

distance.

Controlling

the Tempo

“Controlling the

tempo” is just as important in fencing—it’s one of the main ways you set an

opponent up—introduce a lull and then strike with lightning speed. Alternately, up the tempo to get the opponent

flustered, tense and twitchy, then parry with authority when they overcommit

and riposte cleanly and calmly. Feints

to get the opponent accustomed to a pattern, in order to

break the pattern and strike a half beat before or after. These are just a few of the most basic

examples.

An accomplished

Sword Dancer who practices the real art is simply going to be better equipped

to contend with straightsword, which unlike sturdy single-edged blades are not

durable. Straightsword depends on

finesse as opposed to brute force, and this is especially true in unarmored

combat where one has nothing to protect oneself but the sword.[xxi]

Controlling

the Space

If you’ve ever

pushed hands with a true master, you’ll note that one of the basic things they

do is “control the space”, often in subtle ways. This guarantees them superior

leverage and is a key reason younger, stronger players cannot contend.[xxii] Even lesser masters, if savvy, will employ

this technique.

Dance, better

than any other art form, teaches you to control the space because you work to

hit the same spots on the practice floor every with repetition, and maintain, close or increase distance with other performers. In performance this is even more crucial,

where hitting the mark corresponds with lighting. In film productions, where the budgets can be

hundreds of millions of dollars, missing a mark can cost thousands or tens of

thousands.

With martial

dance, which is exhibited in a variety of settings, often informal, you also have to adjust the steps and distance to adapt to different

spaces you may be performing in.

Sometimes, in the Chinese art, the audience can be very close. You need

to adapt to the space to avoid cutting them!

We’ve had performances with children in the audience sitting one foot

away from flashing swords!

It was only by

controlling the space and matching the tempo that Xiang Bo could forestall

Xiang Zhuang indefinitely and preserve the emperor. It was only by coming close to the partner

with the sword that the fight depicted in Fig. 4 could be convincing.

Figure 4 Michelle Yeoh and Zhang Ziyi in "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" (2000),

Choreographed by Yuen Woo-Ping

Choreography

One school of

thought maintains that we should preserve the forms, as is, never making

changes over subsequent generations, even as the martial environment changes

around us. We might call this “the

Orthodoxy”. In contrast, the idea of

“embracing the heterodoxy” means we should be open to different ways of doing

things, and continually seeking to improve and refine the arts.[xxiii] However, changes to martial forms cannot be

undertaken lightly[xxiv]—this

is a domain that requires what we sometimes call “a true master”, a person who

occupies a place at the pinnacle of the art and can thereby push it forward. Yu Chenghui[xxv]

was such a master and revived the wudang longsword, which had been lost for

generations. Yuen Woo-ping is another

such master who advanced the art of fight choreography in both Asia and the

West.[xxvi] Li Jinglin and Li Tianji were true masters who advanced the sword art in

their generations. [xxvii] Bow Sim Mark is another such master who routinely choreographed new

performance routines and martial forms, and like her teacher Tianji, and his teacher Jinglin,

advanced the sword art in her generation.[xxviii] She was equal to her teachers[xxix]

in internal technique, as a student who had “mastered everything they could

teach”, but she mastered it while still young, and thus had the potential to

surpass. By the time she went to study

with Tianji at the Beijing Institute for physical

culture, she had a couple decades of hardcore, daily Fu style waist training,

and significantly greater flexibility, so could simply do more.[xxx]

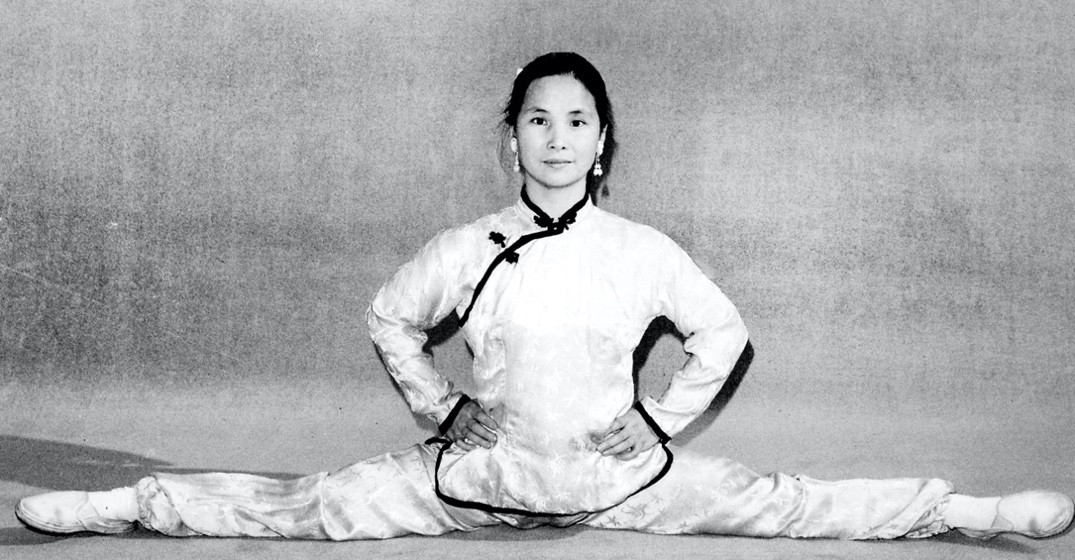

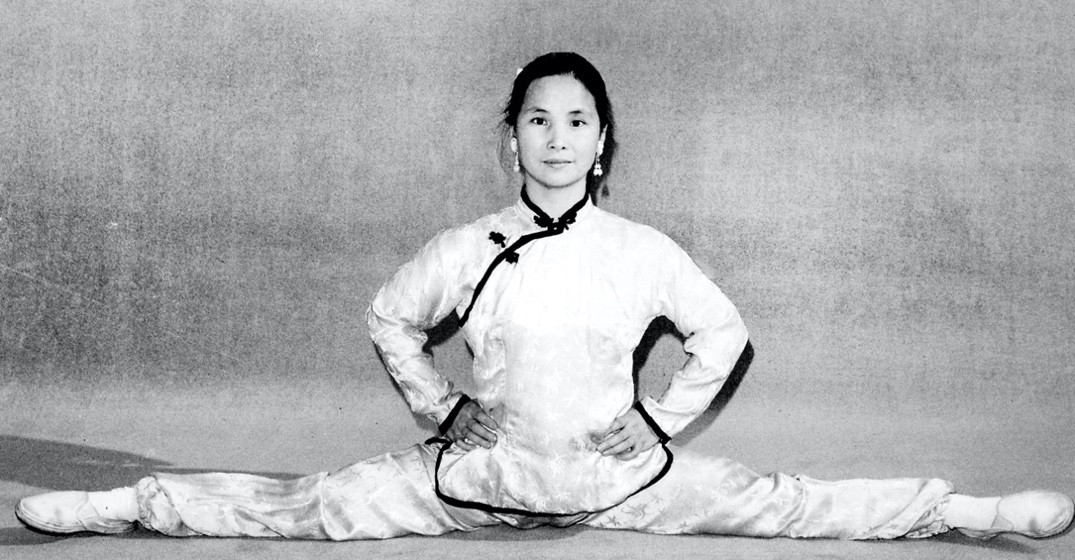

Figure 5 Bow Sim Mark in side

split

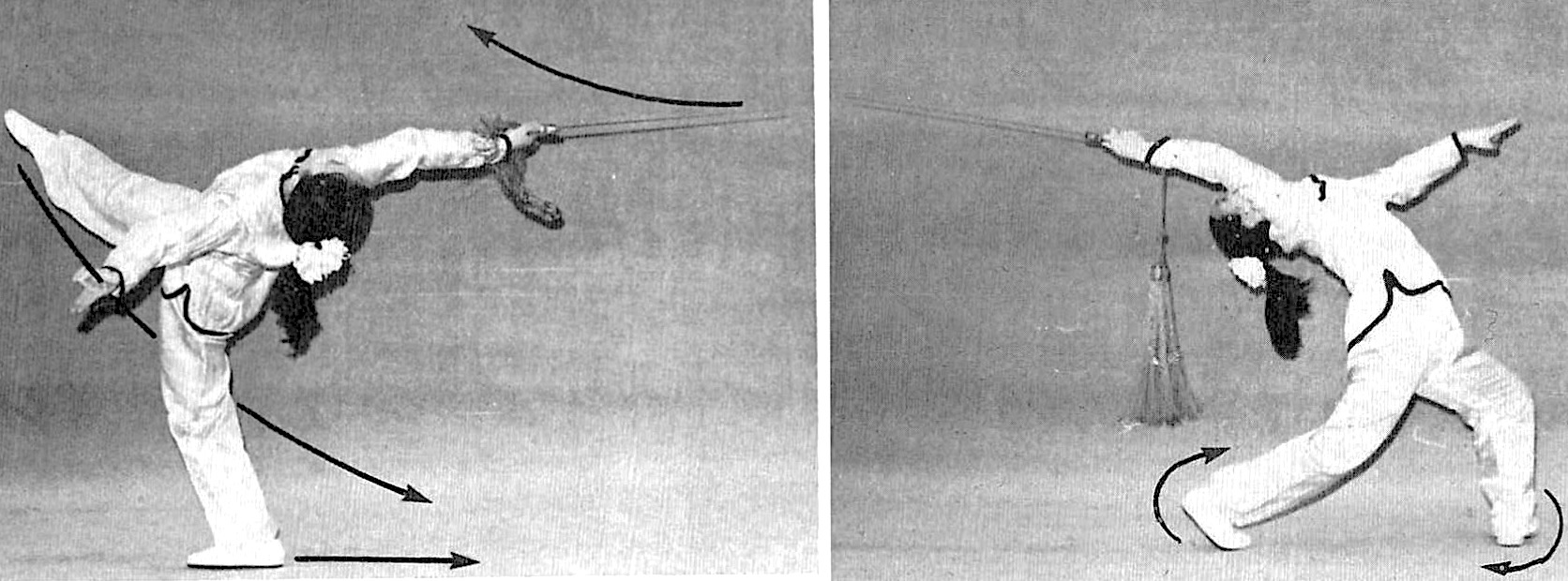

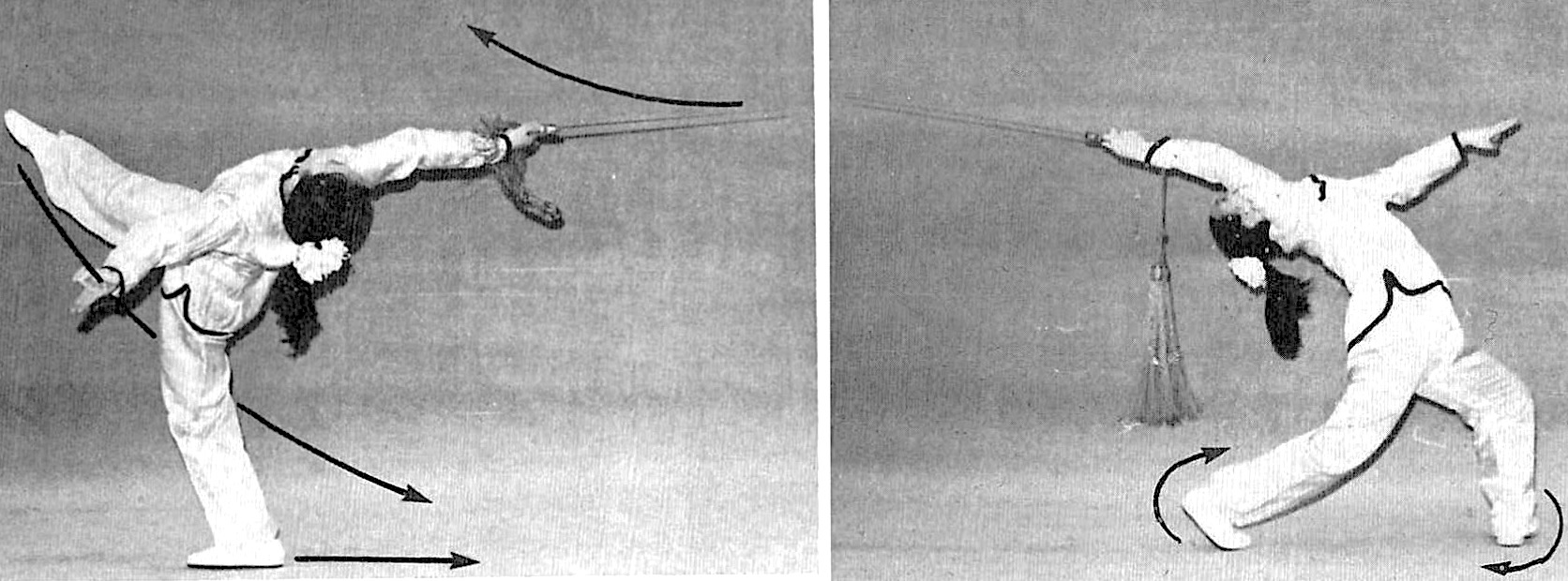

Figure 6 Bow Sim Mark demonstrating Advanced Sword

at 40 (circa 1978)

She had the

shoulders of her teachers and their teachers to stand on. As she once explained, her sword art was the

product of three generations of improvement.[xxxi]

The art of

choreography trains the practitioner to think creatively. Being able to fight creatively provides a

significant advantage—hitting an opponent with something they’ve never

encountered before and are thus unequipped to deal with. This is a quality we see in greats from

Muhammad Ali to Bruce Lee to recent MMA phenom McGregor. [xxxii] True masters must be creative so they can

push the art forward with new methods of movement, applications, and

expressions of technique. This holds

true for any art form.[xxxiii]

To remain vital

and relevant, the arts must be advanced in every generation.

Wushu

Theater

The best fight

choreography is narrative, in that it contains its own story arc within the

series of movements that comprise an extended fight sequence.[xxxiv] This is also what Bow Sim Mark meant by

“Wushu Theater”: telling a story entirely through martial movement.

Wushu Theater is

often conflated with traditional Chinese opera, and thereby dismissed, but it

is distinct from Opera in that all movements and techniques must have real

martial application. Opera, by contrast,

is so stylized that the movements lose most of its martial value. Still great training, as evidenced by the

Seven Little Fortunes, but not quite the real thing. The main critique of the Shaw Era, and

perhaps the pre-SPL era in Chinese Kungfu films in general, is that the

movement was so stylized it was “Opera”.

But this Opera

influenced choreography, of which Yuen Woo-Ping may be the greatest exemplar

notable early for his groundbreaking leg grappling sequences, wowed

generations, created the international fan base, and paved the way for the

newer, more realistic action that was possible with the post-Matrix camera

tech.[xxxv] Smaller, lighter cam finally allowed brash

young action directors to “get inside the choreography”.

Nevertheless, the

development and preservation of choreography in Chinese Opera and Sword Dance

provided the foundation for complex action choreography integrating narrative

arcs. Where William Hobbs[xxxvi]

was an outlier in Western Cinema, in Hong Kong Cinema, such choreographers were

not uncommon, and there are many greats.

True Wushu

Theater has even stricter requirements than film choreography, which can be a

mix of real and embellished[xxxvii]

This new art form

has been widely misunderstood.

Figure 7 Bow Sim Mark as White Snake, based on the

famous Chinese Opera.

The distinction is that every technique she employed in her performance was

real.

Application

vs. Performance

One of the most

effective techniques in Wudang fencing is the “wrist cut”, which comprise the

majority of the basic techniques in the modern “Essentials of Wudang” (Wudang

Basics) manual that comes from Li Jinglin’s student

Huang Yuanxiu.[xxxviii] The most effective of these involves pressing

the blade into the opponent’s tendon and drawing the blade across the limb by

turning the waist to cut—it can look quite elegant but would be determinative

if applied for real, taking away the use of the opponent’s sword hand and

ending combat.

This is

considered “more gentle” than other straightsword

applications, which I will not discuss in detail here for fear of shocking the

reader. [xxxix]

Suffice it to say

that the real application of sword is brutal, ugly, and taking human life is a

terrible thing. When I asked Bow Sim

Mark why so many of her traditional wudang Sword Dances were set to sad music,

she replied “The sword is heavy”. This

carries a double meaning in the sense of the inertia (weight) the internal

practitioner puts into the blade, and the gravity of the martial intent, which

both she and the Zen Sword Saint[xl]

reduce to “taking human life”.[xli] Thus we love Sword Dance because it provides

a domain for a beautiful & peaceful expression of this exquisite art, which

our goal is to preserve.

Conclusion

To apply martial

arts well, the movements and techniques must all be second nature, coming out

of muscle memory b/c there generally isn’t time to think. When the movements can be done without

thought, it allows the practitioner to consider other dimensions, such as

strategy and physical cues from the opponent (foot position, body alignment,

breathing, etc.) The most celebrated

boxers have been able to incorporate showmanship, giving a little something

extra, to the delight of spectators and fans.

This can arise out of greater natural ability, but it will only be

lasting where it arises out of superior technique. High-level Sword Dance requires the

practitioner to perform at that level–not only executing the movements

correctly and well, but conveying the meaning of the movements, putting feeling

into the sword, matching the music, controlling the space, and commanding the

attention of the audience. Sword Dance

is an exquisite art and an exceptional method of training for both boxing and

swordplay.

By

J. Michael Nuell, January 2023

Figure 8 Bow Sim Mark in “swallow tail

balance" with double swords—

in later years she performed traditional wudang Sword Dance with two

longswords,

then switched to longsword and fly-whisk because two

weapons of equal weight was not challenging enough!

[i] Lorge, Peter. Chinese

Martial Arts from Antiquity to the 21st Century. Cambridge

University Press. 2012. pp. 62-63. Excerpting from Sima

Qian, Records of the Grand Historian and Ban Gu, History of the

Former Han Dynasty.

[iii] Ibid. p. 104, 131The great poet Du Fu

lavishly praised Lady Gongson’s Sword Dance. Lorge speculates that her movements must have been

consistent with real fencing in that the audience of aristocrats would have had

some knowledge of that fencing.

[iv] Altenburger,

Roland. The Sword Or the Needle: The Female

Knight-errant (xia) in Traditional Chinese Narrative.

Peter Lang AG. 2009. “Xia”

means “knight errant” and “Nuxia” refers specifically

to the genre of wuxia involving female knights.

[v] See: Condor Heroes, Jin Yong (aka Louis Cha)

[vii] Harrison is the first American to win

Olympic Gold in Judo, and one of very few athletes in the history of the games

to win gold in multiple games, first in 2012 then in 2016. Currently, she is participating in

professional MMA and absolutely dominant with an

undefeated record. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kayla_Harrison

[viii] It is not unlikely that contemporary

Wushu, which could focus on grace and speed, as exemplified by the Northern

Shaolin form, women had a domain not based in raw size and strength where they

could exceed anyone with enough hard work.

Unarmored combat with swords and internal arts in general are two such

domains, where technique, strategy, balance, timing

and footwork are pre-eminent. The distinction of external boxing is that

greater size and strength are generally determinative. Wing Chun is said to have been developed by a

Shaolin Nun to counter this advantage.

Modern attempts to downplay the importance of the origin myth are

immaterial as a

characteristics of the art in general is the neutralization of

size/strength advantage. The point of the myth is that it can be wielded effectively

by a “woman against a man”, which connotes a likely smaller/weaker participant

prevailing against the bigger/stronger, empty hand or with weapons. There is a

reason double dagger is predominantly taught to girls.

[xi] The Buddhist White Peony Temple

in Inner Mongolia is distinct from the Taoist sites in the Wudang Mountains in

Hubei province. 五當 vs. 武当. It’s

unclear to what degree women may have been excluded, especially in the

neo-Confucian Imperial sponsored temples, but chauvinism in the martial arts is

undeniable, and persists even to this day.

A straightsword in an unarmored context is one of the best equalizers in

martial history. A woman can be just as

quick and fierce as a man, and it doesn’t take much strength to wield a light

blade such as a poignard or flexible jian. Fans of modern fantasy may recall that Arya

Stark’s blade is called “needle”, re: The Sword or the Needle.

[xii] Anecdotally, as a teacher of jian, I’ve found women and girls to have more natural

aptitude for this weapon. There are many

reasons for this, which I may treat in a future article.

[xviii] Both Ali and Leonard say the actual

greatest was Sugar Ray Robinson, and credit him as their true teacher, but much

less footage Robinson exists, so his greatness is often lost to modern fans of

the sport.

[xx] These qualities are present in extant war dances

of “primitive” cultures, by which we mean advanced pre-industrial

cultures. Surviving Polynesian War

dances are an exemplar. The feeling is

expressed not only in the body language but in the face which is trained to be

a terrifying mask. This is a basic

example of psychological warfare, such that we can see that theater cannot be

separated from even warfare. Anyone who

has made a serious study of military strategy knows this to be the case. #HungerGames

[xxi] For this reason, the extant Wudang sword

arts have a principle of “preserving the sword”, which extends even further to

“edge preservation”. Real wudang fencing

never goes force against force, but counters force with circular motion,

utilizing the same core principle as Tai Chi.

The main point of failure in swords is the tang, and this and the

surrounding components of metal swords will degrade over time with use. Swords are distinct from knives in having

“action”, which can be understood as the ability to multiply force using the

balance and weight of the blade. Unlike single-edged swords which can used softer,

more durable metal for the back, which does not need to hold an edge, the

blades of normal straightswords are weaker than

sabers. No straightsword should be thought of as durable, even the stiff swords

over 2lbs. This is the cost of the versatility that makes it them the king of cold weapons.

[xxii] When I pushed with Xia Bohua, then a senior citizen, he would just laugh as I

essentially unbalanced myself. He didn’t

have to take it seriously because I was not his student

so he had no “skin in the game”. Pushing

with Sifu was not as entertaining since there, any relative lack of skill did

not bring delight. In both cases I was

unimaginably lucky to even be in the room.

[xxiii] This is a hallmark of Bow Sim Mark’s son,

Donnie Yen, who, after a decade of rigorous,

grueling basic training in traditional Shaolin “went his own way”. He was qualified to do that, and the result is

that his martial art is distinct—no one else looks quite like him. There is a story told of the time he was sent

to train with Beijing team alongside Jet Li, after having gotten in trouble for

fighting. The coaches are said to have

used him to needle the elite team members into working even harder with some

form of “He’s not even competing and refuses to do he movements in the right

way, so why is he stronger and faster than you?”* Like his mother, he wanted to keep the

Chinese arts current and vital, and so integrated techniques and concepts from

an array of non-Chinese arts. He was also famous early on for innovating a

new form of the “no shadows kick”.

* It’s hard

to know the veracity of the legend or it’s effect, but no one can deny that

something spurred on that now legendary class

that inspired a generation.

[xxiv] When Wushu was formalized as the national

sport of China, they brought together the greatest masters to create the first

generation of compulsory forms. This is

where the Advanced Sword form derives from, arguably still the most technically

challenging. (This form comes from

before the integration of gymnastics in contemporary wushu, which technical

aspects occupy a different domain of pure athletics as opposed to fencing

exclusively.)

[xxv] Yu was also a movie star, famed for his

drunken sword in Jet Li Shaolin Temple (1982) and his longsword in Yellow

River Fighter (1988). One of the last films he made was The Sword

Identity (2011), which explores the idea that sword technique derives from

rod. This is a notion many take seriously, and famous practitioners from Musashi Miyamoto to Bow Sim Mark to Zhou Xuan Yun hold that

a “stick can be a sword”—what matters is technique. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yu_Chenghui

[xxvi] Here it’s a slightly different

domain. Where Yu and Mark are considered

true masters for their movement and technique, Yuen’s true mastery is in the

field of fight choreography and the corresponding action direction specific to

that field. The famous fight scene in

the training hall between Michelle Yeoh and Zhang Ziyi

has a lot of “Hollywood” and also some real fencing.

For instance, you’ll notice that when the girl is on the defensive, she has to block and gains no advantage (“right of way”) for a

riposte. But when she is able to make

proper circular counters (parries) as in real wudang fencing, it shifts

advantage and gives her the opening to counter-attack.

Yuen makes a clear distinction between counters executed with the edge for

extra traction and stiffness, as against the heavy bronze rod, and the more

desirable “edge preserving” wudang counters that use the flat, which has more

surface area to control an opponent’s blade.

He also faithfully displays the real wudang principle, explicated by Li Jinglin, of “inviting the opponent in” and “letting their

weapon get very close to your body.”

Those who know the art recognize that Yuen has a deep understanding of

wudang fencing, even where the requirements of the genre (cinematic) call for

much embellishment. Yuen’s approach to fight choreography has influenced and

advanced all modern action cinema, just as Yu and Bow Sim Mark influenced and

advanced contemporary wudang.

[xxviii] Her snake hsingyi

appears to be a creation adapting movements from Dragon Palm and Shaolin snake.

These are no-nonsense techniques I’ve routinely validated in sparring—no one

can counter it because they’ve never encountered it. She actually called

it “baby snake” because the movements are so simple, and had the children

perform it. It is a bagua/hsingyi fusion form in the tradition of the much praised Fu style bagua/taichi fusion form called liangyi. Most men will reject this form because snake

is considered feminine, but traditional snake was one of the secrets that gave

Bow Sim Mark’s sword that extra sinuosity others didn’t have. Where the best bagua

players correctly use the root of the spine to generate motion and force, Bow

Sim Mark could use the whole spine.

[xxix] She was formally a disciple of Fu Wing

Fay and his great friend from childhood, Li Tianji,

but began her Shaolin training in youth under Deng Kam To, and learned sword

from Fong Nam Yue, a woman who lived as a man and had a formidable reputation.

[xxx] She also had to work even harder because

she was a woman in a male domain. See: “Ode

to a Pomegranate Flower” by Wang Anshi. This Song Dynasty poem forms the basis for

the modern Chinese idiom of women in the workplace and other male dominated fields, and gives the name to the swordplay ideal of the

“single drop of red”, which will be explicated in a future essay. For now, suffice it to say that there is a

deep cultural connection of women and jian in China,

from Tang and Song dynasties onward.

Notes

on Figures 5 & 6: Her flexibility allowed her to do an

instant “level change” into a front split and thrust her blade up into the guts

of a charging opponent, one of her signature performance movements. Only women

can go fully down in the front split—men can’t get the same perfect root

because we don’t have the right hips.

The leaning

thrust in Fig.6 on the left Is followed by a wave counter, slice, then drawback

counter that leaves the fencer ready for a forward jumping thrust. Because she

could lean back so far, she could get an extra foot of range compared to other

internal sword masters. (The wushu

competitors have similar flexibility, but these are young athletes and not

high-level internal masters. Mark is the

only true internal master I know of who maintained that level flexibility, not

only though middle age, when most masters stop training, but into her

70’s!)

The leaning

thrust in Fig. 6 on the right is set up by a cross-step chop that can be used

to bind the opponent’s sword, press upward during body turnover, then a

backhand ankle cut, nearly impossible to parry. The fencer never turns their

back on the opponent and maintains blade-on-blade contact throughout the body

turnover. Thus

there are applications beyond the simple surface-level backbend thrust, as with

many movements in Wudang.

These

movements come from “Advanced Sword”, the first compulsory wudang sword form in

the then new sport of Wushu. It contains sequences from the best of the best,

including Wang Zi-Ping (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wang_Zi-Ping)

and Li Tianji.

It was the most technically difficult sword form to date,

and may still be in that the trend since has been toward simplification,

replaced competitive Wushu largely with increasingly technically difficult

gymnastic elements, more suitable for Olympic competition. Bow Sim Mark published a manual on the form

in 1980 featuring two-person work with the young Donnie Yen. It’s a squarely modern fencing form with

sophisticated point-fighting.

Traditional forms from earlier eras typically have only basic point work

and are more heavily oriented on cuts.

Notice also

that Figure 6 is not high-speed photography—Master Mark had to hold those

positions. She explained that to be able

master techniques in internal art, the practitioner had to be able to execute

them slowly as well as quickly, and hold every position in the movement, especially

the balance positions, for an indefinite period. As a famous contemporary

Taoist Wudang master put it: “Bow Sim Mark is strong!”

[xxxi] Li Jinglin ⇒ Li Tianji ⇒ Mark Bo-Sim

[xxxii] Although a problematic figure, no one can

deny this Irish Pugilist’s mastery of showmanship. When McGregor turns his back

on Diaz in the ring, again and again and again, it has meaning. He’s expressing scorn and disrespect—you

should never turn your back on an opponent, but he’s doing it not just via the

action, but with body language that explicates the meaning of the action. There is an element of pantomime

(showmanship) in McGregor’s movement. In

the science of theater we might call this

“gesture”. He is conveying information

to his audience and opponent. And Wesley

Snipes, a celebrated actor is very well regarded in Karate circles because he

trained hard, anyone could look at his body and see he could take punishment

and hit hard. His movement was

disciplined, strong and rooted. Like all

real masters of any level, his movement was clear. And he brought that extra something

that even most martial artists don’t have.

[xxxiii] The principle holds also in every domain

of human endeavor, including mathematics. Every advancement in mathematics is

the product of creative insight, and this is why we

still remember names such as Euler, a towering

figure in his field, even by modern standards.

[xxxiv] The most brilliant example may still be

the training hall sequence from

Crouching Tiger, which has its own narrative arc, and explicates the

martial principle that strategy is preeminent—more important than youth or a

better weapon. This idea is a reflection of Sun Tzu’s Art of War, of Musashi Miyamoto’s Five Rings, and we see it in

modern domains such as prizefighting with Ali’s “rope a dope”, which he used to

defeat stronger opponents, and in the history of insurgency in the 20th

century.

[xxxv] Woo-Ping, of course, also choreographed

the Matrix, which again set the martial world on fire.

[xxxvii] A polite way of saying fake. The requirements for cinema are different

however, where suspension of disbelief is facilitated by editing and, more

recently, computed generated imagery (CGI).

More importantly, in the cinematic medium, the audience requires

spectacle. Wholly realistic martial

films such as The Duellists (1978) may gain

immortal reputations, but they are rarely blockbusters. Cirque du Soleil has dipped their toe into

this domain, but there the martial art is secondary to the acrobatics and

dance, so not true Wushu Theater. The

same is true of the Shen

Yun dance repertoire, which can have a martial flavor because they

interpret the Classics such as Outlaws of the Marsh and Journey to

the West, and perform a version of the Mulan legend, and can be confused

with true Wushu Theater.

[xxxviii] Huang Yuanxiu. Essentials

of the Wudang Sword Art. The Commercial Press, LTD, Shanghai, 1931. [trans.

Paul Brennan, 2014] Those interested can also check out Brennan’s translation

of “The Sancai Sword Manual of Xu Yiqian”, but

understand these manuals only scratch the surface.

[xxxix] Pressing the blade into the flesh is a

natural function of wudang straightsword, where all movement comes from the

waist. Because the arc of the

waist-driven cut is circular, but the blade is straight, it naturally presses

into the opponent’s flesh to cut deeply.

[xl] Musashi

Miyamoto. Historical accounts credit him with prevailing in over 70 duels, each

comprising a life or death struggle against an experienced opponent wielding a

razor sharp sword.*

Most of Musashi’s duel can be assumed to have

been conducted without armor, such that even small mistakes can be instantly

fatal. In Musashi’s

case that was the misfortune of every opponent.

A European mythical referent is Cyrano, but we can see how in Japanese

and Chinese culture, sword is integrated not just into culture but religion,

such that Musashi is regarded as a Zen saint.

Parallels in Tibetan and Chinese Buddhism are sword wielding Arhats. Manjushri is sword wielding

bringer of mercy (bodhisattva) who vanquishes illusion (maya) with his

sword. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miyamoto_Musashi

*Musashi himself, like Bow Sim Mark, could also do it with a

stick. In his most famous duel he cut a tree branch to

match the longsword his opponent was using, charged him with the sun at his

back, and killed him with a strike to the head. This is one of the ways to

identify a master—it doesn’t matter what they’re holding in their hand.

[xli] While it can be common for young men to

glorify violence, the application of this art can be thought of in a technical,

dispassionate way, similar to how a surgeon approaches

their profession. This has been

explicated in literature including Chabon’s Gentlemen of The Road and

the Aubrey/Maturin series. Understanding

of physiology would have been a requirement in the age of sword, but even for

the Sword Dancer it is necessary to have a basic comprehension, and vital to

understanding the meaning of the movements in order to

express them truly. It is possible that

coming to understand the martial use and application of the sword can have a

sobering effect, over time diminishing any tendency toward fantasy by

reinforcing the reality. This was certainly true my own case, beginning as a

teen fantasizing about swordfighting, who by way of

one of the great teachers, came to learn the real art of swordplay and thereby

found peace. Amituofo! 阿弥陀佛

“Shantih,

shantih, shantih.” शान्ति शान्ति शान्ति