Myths

vs Reality

This is a complex subject because myths and legends can be a tool

in attracting students to the arts, the fantasy knights errant and immortal

masters. But it is helpful to separate the

fantastical from the concrete and verifiable, both in the practice and

application, [i]

and in the origins.

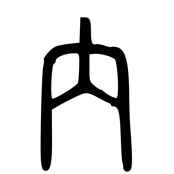

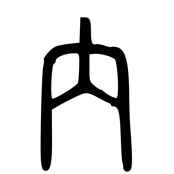

Many ai chi schools still list Zhang Sanfeng as the

founder of Tai Chi, but the discipline of 20th century history has

rendered what was once considered historical mythical.[ii] Now that we have we have modern historical

research, the more rigorous schools like to reference Chen village as

the first documented source of the art.[iii] Tai Chi then spread, and new lineages arose,

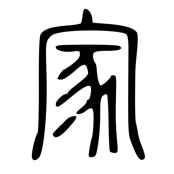

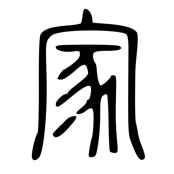

such as Yang,

Wǔ,

Wú, Sun, and

all the myriad styles, but we can only reliably talk about that development for

the past few centuries, with most of what we know coming from the last.

Wudang sword appears to have

evolved independently around the same time as Tai Chi, [iv]

roughly corresponding to transition from the medieval era of armored combat,

potentially in response to outdated force-against-force medieval weapons work.[v]

Song Wei-I is currently

considered the first reliable account of a practitioner of Wudang Sword, but

that may only be because he was secular,[vi]

not removed from the world like the Taoists who inhabited the mountain

wildernesses.[vii]

Boxing/grappling and weapons play

are distinct, where the former have limited uses in warfare, such that the

empty hand arts and weapons art may have initially been practiced by different

groups for different purposes specific to their professional needs. For instance, there are certain domains where

it is useful to be able to subdue an opponent without killing or maiming, a

difficult prospect when one’s weapon is the sword. At some point, certainly by the modern era,[viii]

the two internal systems connected and straight sword

became the primary weapon of tai chi.[ix]

Serious academic research into the

historical origins will doubtless continue and deepen our understanding of the

origins in the years and decades to come.

At present, the earliest manual we

have on internal arts comes from the late 17th century,[x]

so that’s really as far back as we can currently trace

it.

[i] In times past, many travelling martial

artists would perform in cities, towns and villages

for coins, similar to modern busking. To

draw an audience, it was often necessary to embellish the performance to

captivate the crowd. Thus

techniques not particularly useful, or even viable, might be exhibited. Sometimes they were straight up tricks, similar to modern stage magic. These are known as “medicine shows” from the

English term to refer to sellers of snake oil in the old West. The peril is

that if one learns martial art not based on sound physical principles it is

unlikely to serve the practitioner when they need it for self-defense. All

practitioners should therefore be research in the mechanics of the art,

testing, validating, and ideally refining.

[ii] Chinese history in the Imperial era was

generally pseudo-historical, infused and inseparable from legend. A parallel in the West would be Herodotus,

and the field was all but lost in Europe during the Dark Ages.

[iii] This may be because we feel that

propagating non-factual information without context can undermine the teaching.

[iv] This is speculation on my part but the

waist techniques of traditional Taoist Wudang sword have a slightly different

quality than most Tai Chi. This can be

seen clearly in sword uppercuts, which have a strongly vertical motion, extreme

twisting of the waist, and extra extension.

Tai Chi sword uppercuts are usually executed with the torson square with

the opponent. The added extension of

wudang waist is considered “not calm” in orthodox tai chi. Tai Chi, like

wudang, involves very close fighting and optimally cuts from inside the

opponent’s guard after countering, but wudang uses fully extended thrusts,

distinct from tai chi, and many of the traditional wudang techniques have use

against spear. This the wudang practitioner requires extra-extension, as wudang

sword or spear thrust should be faster than a punch or kick. The more extreme waist has added utility against

heavier weapons, especially in fast fighting, due to greater momentum. Extreme

waist verticality is an element of Fu style Tai Chi, but that style developed

out of Bagua, over the period Fu Zhensong was exchanging

information with Li Jinglin. Tai Chi sword conservative (risk averse) than

traditional Wudang, which is significantly more dynamic, physically

challenging, and practiced at a quicker tempo.

[v] More speculation on my part, but brute

force has much higher utility in armored combat, where protective gear can

absorb and turn weapon strikes. Once firearms start to emerge, mobility

displaces armor as a primary consideration of warfare. In unarmored swordplay,

life and death can be the matter of an instant, thus quickness and flexibility

become more optimal than brute force. We

see a parallel in the rapier supplanting longsword for dueling in Europe, and

smaller arming swords supplanting heavier medieval weapons. Modern Wudang

practitioners generally prefers light, flexible blades optimized for slice and

thrust.

[vi] The secular branch of Wudang appears to

have spread the art in that those wishing to learn no longer had to travel to

remote locations. Song Wei-I’s most

famous disciple Li Jinglin was one of the founding members of the Central Guoshu

Institute, and is said to have taught hundreds if not thousands of students,

such that much of modern Chinese internal sword derives from him.

[vii] A wudang priest related to me that many

of these practitioners may not have been practicing Taoists,

but went to the mountains to get away from the government. This would

also explain the lack of formally recorded documents.

[viii] Song Wei-I is credited with introducing

sword art to Chen and Yang Tai Chi.

[ix] However, orthodox tai chi sword typically

lacks traditional wudang elements. Here we have the distinction between Wudang

as a specific art of sword, originating with travelling Taoists, refrencing Wudang Mountain, and

“Wudang” as the umbrella term for the body of Chinese internal martial arts in

the modern Guoshu/Wushu era.