"Initially, in China the novice walked the circle for an hour a day. Although the knees must be well bent before mastery comes, at first bend them only within the confines of comfort. Even this will tire you—an hour of Pa-Kua walking equates to an hour of the most strenuous sport known to man."

-Robert W. Smith from Pa-Kua: Chinese Boxing for Fitness & Self Defense

Smith highlights a very important aspect of internal arts in general. Sifu once quipped, probably because I was pestering her with questions:

"You want to know the secret of Wudang? Bend the knee."

"But Sifu," I replied, "We bend the knee in Tai Chi. How is it different?" To which she answered: "In Wudang we bend the knee more."

Mr. Smith's landmark book is likely the first on bagua in English, and many martial artists in my generation, including myself, credit him with sparking our interest in the art. In book he his explicates the technique via alignment (body frame) and application, and this is consistent with the way bagua is generally taught.

However, practitioners will not be able to make full use of the stepping unless all motion is powered by the waist, because the practitioner will not be able to maintain root while stepping.

What we mean by root in stepping is the action of using the waist to push down into the into the back leg, which momentum rebounds to propel the leading leg forward. In this manner, a practitioner can uproot and opponent in transition and while remaining mobile.

This is exactly the same Tai Chi principle Mr. Smith explicates in other writings, sometimes misinterpreted as "a mystical force of qi travelling deep into the earth and back up to be redirected into the opponent." A more meaningful interpretation is the practitioner redirects the opponent's force (kinetic energy) downward into the rooted foot, a mechanical function, and using the ground as the base, rebounds that energy into the opponent.

We can't fault Mr. Smith because. Reviewing Sun Lutang's book on bagua, the technique is similarly not explicated, only hinted at in the sense of notions like "continually pushing with the palm." All modern masters seem to have some form of this technique, but the technique itself is fundamental to Fu. Fu was, of course, a close colleague of Sun. They exchanged information and the families maintained a link over subsequent generations. Prominent 4th generation teachers in the US are close students of both lineage holders top practitioners of both styles. Fu seems to be the only major style of bagua with highly specialized waist training as foundation to the circle walking, and it clearly distinguishes Fu practitioners.

One key technique that comes from internal stepping is controlling the elbow of a bagua partner to coil behind them and control the throat and base of the spine. Another is to use the step with push to uproot and maintain the partner in a perpetual state of unbalance without exceeding the tipping point indefinitely as the practitioner pushes them back at a walking pace, maintaining sticky.

What we mean by root in this technique is technically a pulse. Root waxes and wanes in each step, broken up by a single moment of transition with no root. Yet even in that instant of of total commitment the foot, always flat, maintains contact with the ground. Practitioners who have developed sufficient tendon flexibility are able to keep the back foot flat until the weight is transferred fully to the front. The only time the foot is not flat, either spinning or walking, is the outward hook step. Even there it is ideally executed with ground contact in the manner of "kicking dust".

That flat-footed skimming walk is commonly known as some form of "Mud Walking Step" and is said to come from Fu bagua, from which we also get Dragon Palm.

However teachers in past generations were either keeping secrets,¹ or the stepping technique was refined and improved in subsequent generations by Fu's son, Fu Wing Fay, who went much deeper in Tai Chi than his father, having learned it in boyhood with exposure to the top practitioners of the major styles. Regardless, where we typically evaluate a teacher by the quality of their students, it is undeniable that Bow Sim Mark's reputation is well deserved, as is Fu Wing Fay's. The foundation they taught is effective.

The term we use for this kind of bagua walking is Ripple Step.

This is the term used by Victor Fu Sheng Long, the 3rd generation Fu style lineage holder, and Bow Sim Mark, top 3rd generation disciple of Fu Zhensong and Li Jinglin.

Ripple step connotes the pulsing action that is the core of the applied movement from a true internal sense. Without this action the stepping is merely external walking with internal body alignment and no real connection (i.e. waist) via the root of the spine, where power is generated.

Ripple step describes a mathematical function that can be expressed in classical mechanics as a form of sine wave. The oscillation and interval of the waveform can vary, in that we can increase or decrease the speed or length of the steps. The head should remain level in stepping because the force generated is linear, even where the stepping is circular. This linear force can transition into a spiral, when a third dimension is added. Striking force will always be linear; countering force will always be spiral or some form of eliptoid. We don't have to be able to do the math on paper, but we do need to come to understand it intuitively through dedicated training over an extended period.

Mudwalking step, although it has the appearance of "skimming the foot across the surface" actually connotes forward motion without out lifting the foot out of the mud. This means pushing the foot forward against constant resistance, which requires the toe to remain pointed and the foot perfectly flat. If the foot is not perfectly flat, it will rise or sink as it moves forward, displacing the center and breaking the root. Further, this motion cannot be effected with the muscles of the stepping leg, or even effectively using the muscles of the back leg as external practitioners do it, because the back foot has insufficient traction. Only by pushing down with the waist into the rooted foot can the body be propelled forward.

If you master this technique you can do advanced wudang on slick pavement, including lunges and and jumps. The key is being able to push directly "into the earth" with the waist so that the foot does not slip, even on a slippery surface.

If the bagua step is quick but not powerful, meaning that it can't uproot continuously and therefore can only be used to evade, it is form without substance, as are any external applications of internal martial arts.

You need to practice both linear walking and walking in a circle. The linear form is necessary, as exemplified in Fu Dragon Palm and the ripple steo is what distinguishes linear bagua walking from normal stepping. With ripple, the opponent is uprooted and pushed backwards, maintaining sticky, and a continual state of unbalance in the opponent. Without this capability, the linear walking can only be used to close distance, as in conventional boxing.

A large circle is more applicable to linear walking practice because the toe does not turn in perceptibly. Linear practice has more benefit than walking a large circle.

Small circles are the essense of bagua, which involves stepping around the opponent to attack or evade, always with a potential hook step. Walking tight circles is critical.

Tight circles also allow the practitioner to get dizzy more quickly, in preparation for the Gua. Where a three dozen steps can be sufficient in a circle of 3', on a large circle hundreds of steps may be necessary to create the gravity necessary to get the inner ear spinning.²

Dizziness also helps guide the practitioner into the spiral vectors necessary to apply the art. It requires the practitioner to maintain constant motion or lose sync with the spinning in the head, which breaks the power of the movement, initially psychologically, leading to errors in the frame.

When one begins to attain high-level bagua, which is to say perfect execution while dizzy, one begins to see the roots of the deep art in drunken boxing. In fact, core Fu style waist training techniques derive from Drunken. This is likely the reason Fu style waist technique is considered the best in the martial world, and has produced famous masters for four generations.

Keeping both feet flat at all times, lean back as far as you can and let the action of the waist push one leg forward.

No not use the muscles of the leg except for control—all of the kinetic energy that moves the leg forward must come from the waist.

When leanind back, the back foot is heavy and the front foot is light.

Lean forward, drawing the back foot to level with the front foot. The back foot has become light and the front foot heavy.

Without perceptible pause, lean back to propel the light foot forward.

Repeat this in a linear manner, at least 3 to 5 times if possible, in one direction, then turn around and repeat.

With regular practice over several years, the ripple step will be attained and can be applied to the hook step in circle walking.

NOTE: In normal bagua walking you lose the lean forward and lean back, and just maintain the waist motion. Old-school hardcore Fu style still shows the big waist, but it turns out not to be necessary at an advanced level, and so today is used mainly to explicate the technique.

One of the main differences between the Classical orthodox stepping and Contemporary hetrodox stepping is the latter allows more freedom.

Orthodox: Knees "touching" through the step. This limits the practitioner to small, quick steps only.

Hetrodox: No restriction of length of step, so long as all movement is powered by the waist.

There are other distinguishing aspects, but the will be found to arise from the basic requirement of "knees touching" or not touching.

If the head is bobbing up and down, the center (tan tien) is bobbing up and down, and the linear force necessary to uproot cannot be applied.

A second type of Fu style stepping is often practiced with Yang Palm Bagua, that of kicking with each step. We practice it at 3 levels: ankle, knee, hip.

In this instance of circle walking it is always what we call a "toe kick". Fu style also has a "dragon step" technique that is an oblique heel strike to the inside or outside of either kneecap, always executed after the grapple from inside the opponent's guard. By contrast, the bagua toe kick typically comes from outside, used in the manner of jabs to create an opening. Circle stepping technique with the addition of fajin from inside the opponent's guard will almost always be a hook step, either outward or inward, which is a compact form of sweep. Inward hook step is the most common setup for the single palm change, and is seen in every bagua style.

We call it "advanced" because it is more difficult to do without arresting the momentum of the body at the moment of focus in the kick, but this does not mean it's more optimal, and it definitely puts stress on the joints than the basic ripple step. For this reason it is less often practiced. But it is nasty when employed, and can really mess with an opponent's calm. Even where the kicks cause no damage, they can be extremely annoying and relentless. It can use it to kick the opponent's foot as they are beginning to step forward, and to harass them if they are not attacking. Typically a bagua player employing this strategy will be goadiing an opponent into over-committing.

Fu Style also has a "tiger step" that allows the toe to come up, similar to a Tai Chi step only more rapid. This step can be used for circle walking if mudwalking variant is too challenging. Both are Fu ripple steps, but the tiger step is usually reserved for forms like Tiger Boxing, whihc contains the continuous sticky pushing technique, along with Dragon Palm.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of deep tendon flexibility in the ankles. Without such flexibility, it is unlikely the practitioner will able to express real neijin, and certainly never achieve high-level technique.

Alternating between classica bagua stancework (static) and twisting the waist in the stance is a useful way to condition the tendons.

At a minimum, for real bagua, the practitioner must be able to turn their waist 90 degrees, keeping the back foot rooted and flat.

Everyone talks about twistiing to drill into the ground, but almost no one develops the tendon sufficiently to really able to do it. Only the legit masters can. They have tens of thousands of hours training, the first 10K hours in the first few years. In the contemporary era, these masters are few and far between. Those who continue to train at that level for even ten years is now rare, and for their whole career is almost unheard of. Bow Sim Mark was one of those masters.

Today it's mostly advanced beginners teaching the art, if they teach at all. Students who train hard every day for at least three hours will be advanced beginners for at least ten years. If you slack in training after that period, you will never progress beyond that level.

The only way to develop the real twisting neijin in stepping is to walk tight circles, morning and night. You'll know you're getting it when you start to utilize that technique for all walking, whether in training or daily life.

You'll know it because you'll feel it, but you'll delude yourself into thinking you feel it for at least a decade, probably two in this era, just like we all did.

Unlike Tai Chi, if you only practice bagua a few hours per week, or fifteen minutes per day, you will never get it, even if you practice your entire life.

To do a proper body turnover for bagua, snake, and Wudang sword, the foot must be flat throughout the entire turn, otherwise the body turnover cannot be executed at any speed, fast or slow, held indefinitely at any part of the technique.

High-level internal body turnovers are eyes-on, just like Shaolin, requiring high back flexibility, and the ability to lean back more than 45 degrees. Sifu could go 90 degrees without strain. The strength for this application is built via the linear ripple step training.

Where the practitioner has been uprooted, they may execute a body turnover-like roll, which the same effect of ending on balance, but the quality is different. In the former case, it is a technique of of response and riposte; in the latter it is attacking into the turnover motion to create an opening for a clean strike, eyes on, so that the back is never turned to the opponent.³

Body turnovers are a key counter to wrist locks that derive from Chin Na and Jujitsu which been adopted by mmartial systems around the world. However, the body turnover counters have not been adopted because few other systems do the requisite conditioning. Joint locking does not work against a competent bagua player, and if they actually accept the lock, it's because they're setting the partner up.

Bow Sim Mark Whitesnake, the bagua/hsingyi fusion form, has a stepping exercise to drill the internal form: step/strike, crosstep/block, turnover/counter, root/strike, step/strike, repeat.

When done correctly, applications involviing internal body turnovers are very difficult to counter. To guarantee a bodyturnover in sparring or a real use context one must have practiced it a literal million times, because otherwise the movement won't be natural. For this reason, internal body turnover is one of those techniques that takes more than a decade to master, even with rigorous daily training.

I seem to be unique in this generation in that I was made to walk the circle for three years before Sifu would teach me a single Gua. Looking back I suspect she just didn't want to teach a bagua form at the time, in which she was still refining and her Combined Internal Forms,⁴ because when my stepping was deemed to be minimally adequate, she taught Yin Palm to the entire class, even those who hadn't walked the circle.

Regardless, what she told me was that I couldn't step correctly yet, such that there was no point in teaching me bagua because I wouldn't be able to really use it. When I had practiced enough to step naturally, then I'd be ready.

When I complained to my sihings and tried to get them to teach me and they refused. They felt the requirements consistent with other traditional methods such as Hung Gar, and therefore reasonable. In traditional Hung Gar, as in 36th Chamber real-deal direct disciples, new students were made to hold horse stance three hours every day for a three years before learning the basic movements. Old-school HK Wing Chun had similar requirements. These are methods of not only strengthening the student's body to prepare them for real training, but of testing their commitment.

I'm not going to say I walked the circle every day for an hour for three years because I was 20 and still in school and there were a lot of distractions, but I did walk it obsessively, and practiced my ripple step everywhere I walked, which was everywhere, having no car. This is the same method Sonny Boy Williamson used to master harmonica, walking between towns in the deep South.

As as result, I got to feel Sifu's neijin every session; the students who had not walked the circle sufficiently, even students with real technique senior to me, would be immediately dismissed as partners or never considered at all. I can't understate the importance of feeling the teacher's internal technique on a regular basis over a span of decades.⁵

Very few practitioners today will put in that kind of time, which is understandable if the goal is primarily health, but the takeaway should be that stepping is the foundation of the bagua art, and it should be practiced significantly more than any other aspect.

One hour is good, but three is even better. 1/3 circle walking, 1/6 basic training, 1/6 waist training, 1/6 stanceword, 1/6 stretching is a good ratio for solo practice for those wishing to reach an advanced level.

Use of the legs instead of the waist can create tension, eventually leading to muscle strain or injury as the legs become more fatigued. Whenever tension arises in the muscles, or pain in tendons, the practitioner must relax and rely solely on the motion of the waist.

A common mistake in internal arts is not exhausting the body prior to Tai Chi practice. If the body is not exhausted, how can the practitioner guarantee forgoing brute force? This is especially important for younger practitioner. An hour of circle walking is great preparation for 15 minutes of good Tai Chi.

Additionally:

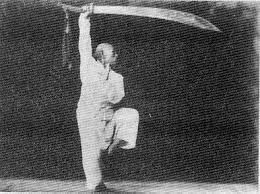

Here is the founder of our Bagua Family demonstrating the basic stance:

Sifu ultimately arrived at a ratio of 5x one-legged to 1x two-legged, otherwise you won't have the root to guarantee advanced techniques on one leg, or the strength to maintain perfect balance over a prolonged period, which can mean an entire day of low stance wudang.

Many bagua forms have toe kicks from a leaning back position. Practitioners must be able to hold that balance position indefinitely, such that, if the movement is to be exhibited or guaranteed in application, the full-extension one-legged stance must be practiced every day for a challenging amount of time, ideally repeatedly until the legs are exhausted, then switch to the next stance.

One legged balance is so critical to high-level bagua, Fu style at least, that it can take months or years for a student to be ready to go past the first guas. Anyone who can do tai chi can do Yin Palm gua one, but to really do gua five, "turning over body palm", you need world-class balance. It is one of those cases where "there is only do or not do, there is no try" meaning there is no in-between "I can sort of do it" with gua five.

Fu Zhengzong is the 1st Generation

Fu Wing Fay is 2nd Generation

Bow Sim Mark & Fu Shenglong are 3rd Generation

Other notable 2nd Generation direct disciples of Fu Zhensong include Lin Chao Zhen and Sun Bao Gang.

Other notable practitioners include Liang Qiang Ya in the 2nd Generation, and Wing Chun Master Kwok Wan Ping of Hong Kong in the 3rd.

Dong Haichuan is the founder of Bagua. Fu Zhensong is 3rd generation disciple, as a student of Ma Gui, Cheng Tinghua and others. Yin Fu, a student of Dong, is the originator of Yin Palm bagua.

⼥⻨颗 | January 8, 2023

Revised, March 15, 2023

________________________________

¹ In past eras, keeping martial secrets could be a matter of life or death. As Ned Stark once quipped: "I don't fight in tournaments because if I have to fight someone for real, I don't want them to know what I can do." In Jin Yong it is common for true Masters to use inferior styles rather than let a potential opponent see their secret techniques, which they keep in reserve for desperate situations.

² Guas rarely begin with a one-legged stance, so the practitioner always has time to "sink the Chi" before one legged balance is necessary, which is the "cheat". Advanced bagua requires going directly from wheel or spin turns, 1080 if possible, into one-legged balance positions. The cheat there is the spins can be as little as 360 degrees, and only rarely strictly require 720 degrees or more. Such techniques are also often executed after spins in the opposite direction, which likely neutralizes to some degree whatever is going on in the inner ear. This capability is critical to be able to say one does Fu bagua at a high level.

³ Such techniques reveal one's understanding bagua and wudang applications. Fu style spin turns are, in almost all real use cases, executed body to body as horizontal rolls on one flat foot. Wheel turns are the vertical equivalent, also flat-footed, used to come up under and inside the opponent's guard to strike unapposed from body to body. Body turnovers are eyes on the strike so that the spine is never exposed. The key point is, real Wudang has no techniques in which the practitioner exposes their back to the opponent. Understanding the use of the movements requires rigorous daily training and correction over years and decades. This is why it is so important to seek a qualified teacher. Merely imitating the movements without understanding the use can be perilous. Learning to train the back without injury is critical, and it is not recommended this be undertaken except under guidance of a qualified fitness professional.

⁴ She tricked me by having me drill all the techniques required for Combined Internal, such that, when I finally learned Dragon Palm decades later, I could do it the first time. I was competent in every technique from decades of daily Fu basic training. The basic training is the most important thing, and it's the part everyone can master.

Sifu told me the secrets and I'm passing that on to the world because intellectual understanding is not sufficient. Most practitioners will not be able to put in the time required to master the techniques. The general standard for mastering a single movement in the Chinese arts is a literal "thousand thousand times". This is not euphemistic. Practicing a movement 1000 times per day, six days per week, gets one to that magic number in about three years. As few as 64 steps between guas will net a thousand steps in well under an hour, even at a slow-motion pace of a step every two seconds. 3600 seconds in an hour is enough to execute 8 guas, left and right, with a minute of stancework at the 16 transitional palm changes, and still get couple thousand steps in at a slow pace of a step per second. At a medium pace, the required time can be cut in half so both Yin and Yang palm can be practied in a single hour, doubling the number of steps.

Because the number of students putting in even this minimal amount of time is today so rare, any teacher of any style should be happy to see a practitioner reach a high-level. That student, regardless of who taught them, will bring attention to the art and help keep it vital in in their generation. "We are all one big family".

⁵ In an art where sticking to the partner is a fundamental requirement, the notion of what has sometimes been called "direct transferrence" is a legitimate, practical, physical notion. This is one of the reasons the art cannot be learned remotely, only the forms. The majority of teachers of internal art can only do the forms and, in some cases, applications. Both are distinct from neijin, and corollary to it. External expression of internal applications will never work against a strong opponent, and, as a result, Chinese internal arts have lost prestige in the martial world. This is because the forms and applications only the surface; they cannot be called truly internal without deep neijin.